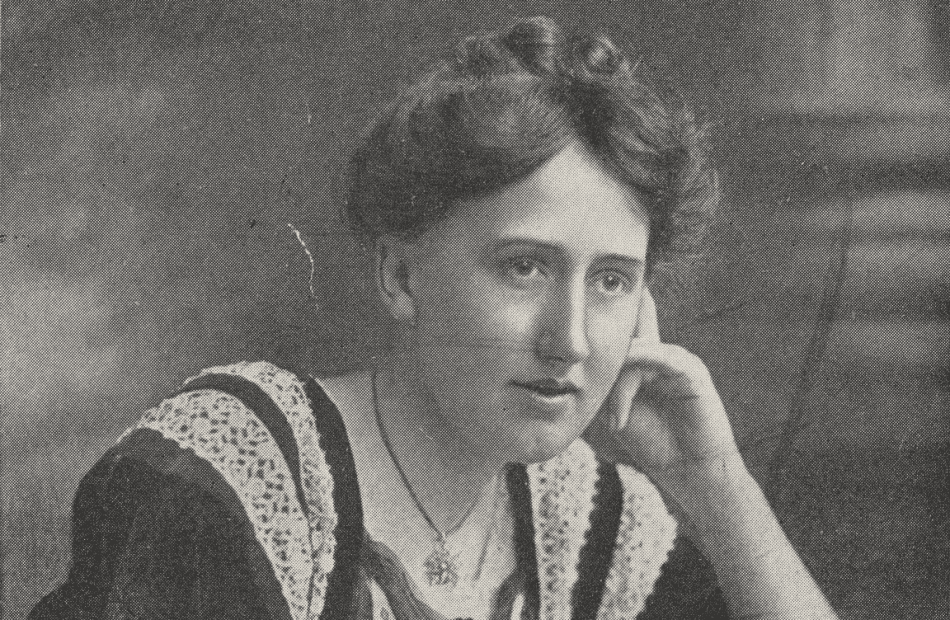

Manchester’s history is undoubtedly closely linked to its industrial past, its factories, mills, and trade. But the city’s story is not limited to this alone. For Manchester is not just about industry; it is about sport, architecture, science, and education. These fields have played a significant role in shaping the city’s identity. This article, in particular, will focus on a figure who was at the forefront of the city’s medical education and healthcare. Catherine Chisholm was the first female doctor to graduate from Manchester’s Medical School. She became not only a leader in her field but also a leading mentor for future generations. She made a substantial contribution to the development of child healthcare, women’s medical education, and the system of school medical supervision. More at manchester1.one.

Early Life: What Influenced Her Choice of Profession?

Catherine Chisholm was born in the small town of Radcliffe, Lancashire, not far from Manchester. She was the eldest daughter of a general practitioner, Kenneth Mackenzie Chisholm, a graduate of the University of Edinburgh’s medical faculty. It is worth noting that at that time, the doors of universities were closed to women, but despite this, her father held progressive views: he was convinced that medicine should be accessible to men and women alike.

From an early age, Catherine grew up in an atmosphere where medical practice was part of everyday life. Her father didn’t just tell his daughter about his work; he often took her with him on his patient rounds. These trips became a real school for the young girl: she saw how medicine could change people’s lives and understood that the profession of a doctor was not only about knowledge but also about serving society.

Her father’s support played a key role in her destiny. At a time when many girls could not even dream of a career in medicine, Chisholm was confident in her choice. It was her father’s belief in her abilities that helped her overcome societal prejudice and enter university.

It can be said that her path into medicine began long before her formal studies: it was born in her family, in a home where medicine was an inseparable part of life. And it was thanks to her father that Catherine Chisholm became one of the first female doctors, proving that medicine has no gender boundaries.

First Steps in Education

In 1895, a young Catherine Chisholm enrolled at Owens College in Manchester. Even then, she stood out for her persistence and thirst for knowledge, which at the time remained almost inaccessible to women. In 1898, she earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in Classics and was awarded the prestigious Bishop Lee Greek Testament Prize for outstanding achievements in the study of the Greek language and ancient texts.

However, the humanities were just the first step. Chisholm did not rest on her laurels and decided to go further, choosing a path that was a real challenge for women at the end of the 19th century—medicine. In 1899, she made history by becoming the first female student admitted to the Medical School of Owens College. It was a breakthrough: the doors of medical education were beginning to open for women, but the path remained difficult.

Despite prejudice and societal pressure, Catherine successfully completed her studies and received her medical degree from the Victoria University of Manchester. Her knowledge and efforts were highly praised: she qualified with distinctions in forensic medicine, obstetrics, surgery, and pathology. Such a broad range of specialisations demonstrated not only her brilliant intellect but also her determination to become a professional equal to her male colleagues.

Chisholm became more than just a doctor; she proved that women could master complex sciences and build a career in medicine on an equal footing with men. Her example inspired subsequent generations of girls who dreamed of becoming doctors and laid the foundation for the further expansion of women’s presence in the medical field.

Further Career in Medicine

After graduating from university, Catherine Chisholm began her medical career as a resident. For the first year, she worked at the Clapham Maternity Hospital—a unique institution for its time. It was one of the few hospitals where all the doctors were women. For Chisholm, this was a continuation of the ideas she had absorbed in childhood from her father, a doctor who believed that medicine should be accessible to women. It was he who had once taken his daughter on rounds and shown her that a doctor’s work involves not only knowledge but also a great responsibility to people.

Chisholm then completed a six-month placement at the Eldwick Sanatorium for Children in Bingley, Yorkshire. This experience became a turning point: she became even more interested in paediatrics and realised that she wanted to dedicate herself to helping children and mothers.

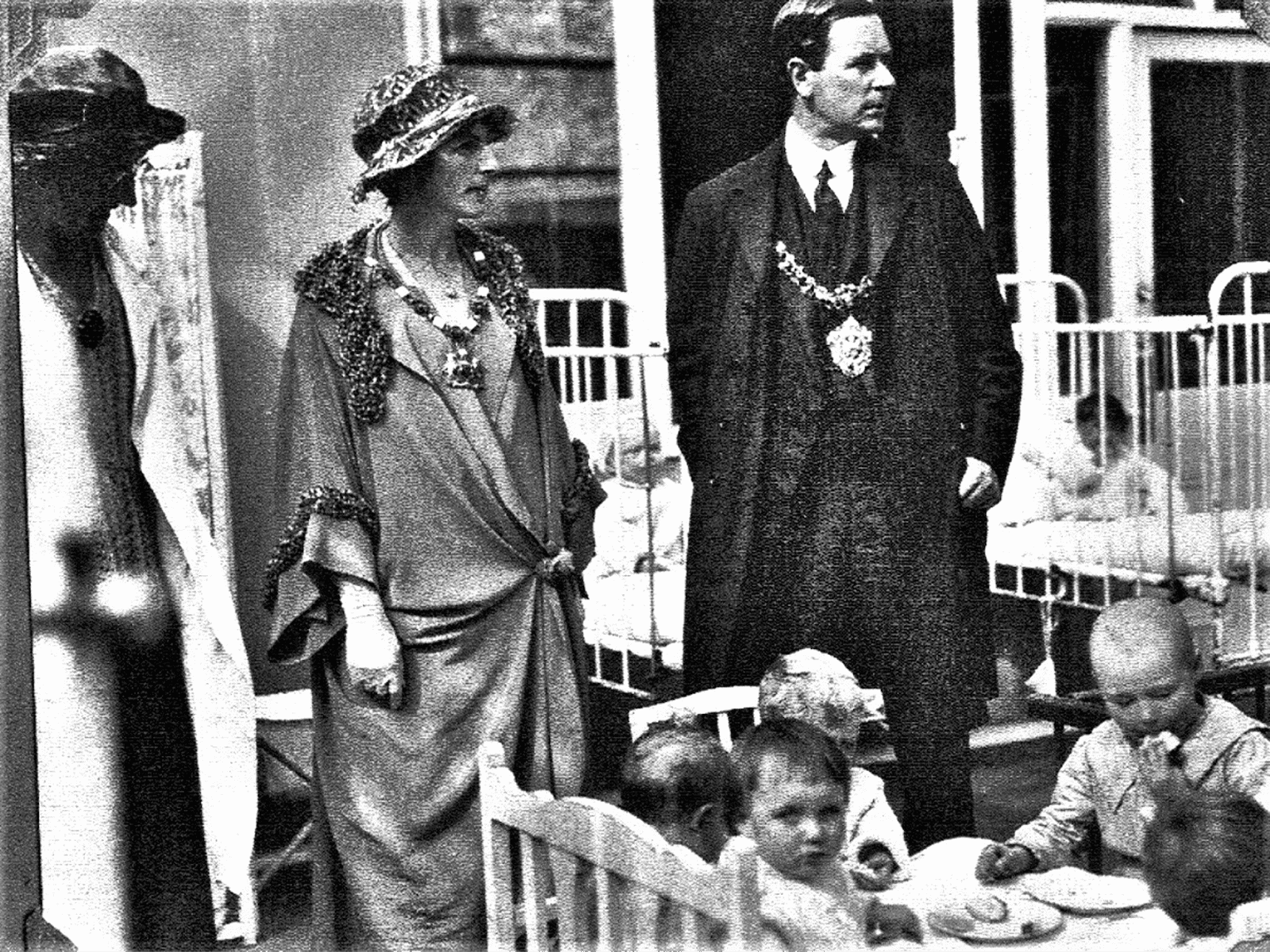

In 1906, she returned to Manchester and opened her own practice. Her clinic served both female university students and local residents. The young female doctor quickly earned the trust of her patients, and in 1908, she was appointed as an honorary physician at the Northern Hospital for Children in Manchester. This position largely defined her subsequent career.

In parallel, Chisholm worked as a consultant at Hope Hospital in Salford and at a children’s hospital. But her main creation was the Manchester Babies’ Hospital. Initially, it was a small institution with only 12 beds, specialising in the treatment of infants and young children with diarrhoea and gastrointestinal disorders. Inspired by the example of a London children’s hospital, Chisholm ensured that, like at Clapham, only female doctors worked there.

Her approach was innovative. In 1920, she visited the Boston Children’s Hospital and brought back ideas that she later implemented in Manchester: a ward for treating rickets was opened, along with a human milk bank, its own laboratory, and teaching facilities. This became a crucial step in the development of British paediatrics.

Contribution to Education

In addition to her clinical practice, Catherine Chisholm taught at the University of Manchester for over 20 years. From 1923 to 1949, she lectured on vaccination and childhood diseases, passing on her experience to new generations of doctors.

In 1949, she became the first female Honorary Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. This was a particularly high honour, as the organisation had long remained closed to women.

Catherine actively fought for the rights of female doctors, becoming one of the founders and a future president of the Medical Women’s Federation. Her dissertation on the menstrual cycle was revolutionary for its time and emphasised the importance of a knowledgeable approach to women’s health.

Catherine Chisholm left the city not only a hospital but also a strong educational foundation. She created an inseparable link between academia, medicine, and equality, and proved that education can be a tool not only for knowledge but also for social justice.

Chisholm’s career cannot be viewed separately from her family. It was her father, a doctor by profession, who instilled in her the belief that medicine should not have gender barriers. His support and example helped Catherine not only to become a doctor but also to open the door for hundreds of other women who followed in her footsteps.

Catherine Chisholm died in 1952 at the age of 74. She played a vital role in the foundation of the Manchester Babies’ Hospital, which contributed to her reputation as one of the founders of modern neonatal practice in the city. And it is thanks to her that medical education became accessible to women not only in Manchester but throughout the United Kingdom, marking a monumental breakthrough of the 20th century.