In the late 19th century, Manchester was a city of contrasts: on one side, glittering wealth; on the other, painful poverty. Its factories roared, chimneys smoked, and its streets were crowded with men and women whose lives were consumed by work in industrial enterprises. It is worth noting that for most working-class women, education was a luxury that seemed forever out of reach. Read more at manchester1.one.

But the situation changed thanks to Esther Roper – a teacher, activist, and suffragist. She believed that education could be the key to a different life. Unlike many of her contemporaries, who focused on the interests of middle-class women, Esther turned her attention to the most vulnerable – those who worked in the weaving mills, laundries, and match factories.

She did not limit herself to words or theories. Roper gave these women real opportunities to learn and develop, opening doors for them that had remained closed for decades. That is why her name is still associated with the fight for equality and the right to education for all, not just for a select few.

Early Life

Esther Roper was born in 1868 in Lancashire, in an era when strict demands were placed on women. She came from a simple working-class family. Her father, Edward Roper, started as a factory worker but later found his calling in service, becoming a missionary. Her father’s new work influenced his daughter. He showed her that life could be changed through hard work, knowledge, and the power of conviction. Her mother, Annie Roper, came from a family of Irish immigrants and knew the value of hard work.

From an early age, Esther saw the example set by her parents – people who lived not only for themselves but also for others. It was from her father that she inherited a desire to serve society and the conviction that even those born into poverty have the right to develop and be educated. He supported her desire to study, which was a real rarity for a girl from a working-class family in the late 19th century.

Esther received her education at a Church Missionary Society school. This gave her a strong foundation not only in knowledge but also in values – the desire to help others, to see beyond her own well-being. Thus, her character gradually formed: purposeful, empathetic, and ready to fight for justice.

It could be said that her father became her main role model. His transition from a factory bench to missionary work convinced Esther that origin does not define destiny.

One of the First Women to Graduate from Owens College

Esther Roper went down in history as one of the first women to receive an education at Owens College in Manchester. Such a step in the late 19th century was a real challenge to society. In 1886, she was admitted as part of an unusual experiment: the university wanted to test whether women were capable of studying on par with men without detriment to their health and psyche. In effect, the young women had to prove that intellectual strain was not solely a male prerogative. Esther not only endured this trial but also became one of the top students.

During her studies, she already demonstrated leadership qualities. In 1897, together with her friend Marion Ledward, she founded the journal *Iris* – a publication for women students. It was published twice a year and addressed the most pressing issues: women’s rights to education, careers, and independence. The journal became a platform for communication between current and former students, a kind of “women’s support network” long before similar communities emerged in the modern sense.

In 1891, Esther graduated from college with honours. Her degree covered Latin, English Literature, and Political Economy – disciplines then considered “masculine” and requiring serious preparation. For the daughter of a factory worker and a missionary, this was particularly symbolic: she proved that background is no barrier to knowledge.

A Career Dedicated to Educational Access for Working-Class Women

After graduating, she did not lose touch with the college. Esther was an active participant in the women’s debating society, where issues of social equality and women’s rights were discussed. In 1895, she took the next step – co-founding the Manchester University Settlement in the Ancoats district. This was a poor, working-class suburb where people lived in appalling conditions. There, Roper helped organise educational courses and cultural initiatives for local residents, giving them a chance for development and self-realisation. She was soon elected to the project’s executive committee.

And all this became possible in large part thanks to her father. Through his own example, Edward Roper showed his daughter that social origin does not define the limits of one’s destiny. He managed to break free from being a factory hand and dedicated himself to serving people, and this idea became deeply rooted in Esther. His belief that life could be changed through work, education, and helping others became her guiding star. That is why she dedicated her career to creating opportunities for working-class women – those who, like her own family, were accustomed to fighting for every chance.

Feminist Activism

From 1893 to 1905, Esther Roper held the position of secretary for the Manchester National Society for Women’s Suffrage. This work became a key stage in her life. Following the death of the prominent feminist Lydia Becker, the organisation was in crisis: it lacked a clear direction. It was Roper who breathed new life into the movement, giving it direction and strength.

Her main achievement was broadening the struggle for education. While the focus had previously been mainly on the interests of middle-class women, Esther boldly took a step further – she involved working-class women in the campaign. It was important to her that the calls for the right to vote were heard from those who worked in factories, laundries, and various industries. She organised meetings where ordinary women spoke for themselves, telling of the injustices they faced. Campaigns, rallies, lectures – all became a reality thanks to her.

In 1897, the organisation changed its name to become the North of England Society for Women’s Suffrage. This step symbolised the movement’s growth: it was now not just a Manchester-based society but a regional association, part of the larger National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies.

Esther saw working-class women not as “victims” but as a force capable of changing society. And this became her main contribution: she transformed the suffragist movement into a truly grassroots one.

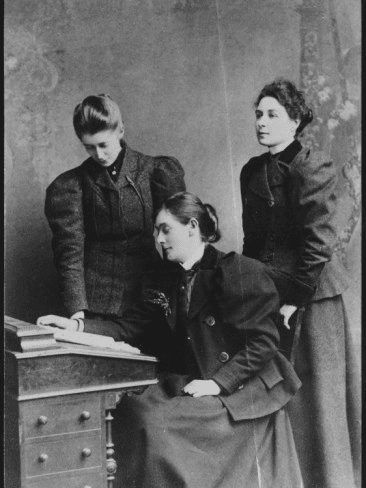

A turning point in Esther’s life was her meeting with the Irish poet and activist Eva Gore-Booth. Together, they formed one of the most powerful reformist partnerships of their time. Living and working in Manchester, they fought not only for women’s suffrage but also for better working conditions, higher wages, and access to education for women employed in difficult or marginalised professions.

Roper and Gore-Booth co-authored leaflets, organised protests, and created support networks for women who were ignored by mainstream reform movements. Their activism combined practical support with far-sighted ideals. They recognised that literacy, self-confidence, and political awareness could change women’s lives just as much as higher wages or improved legislation.

Their partnership also embodied another quiet revolution: a shared personal life founded on mutual respect and love. Together, they challenged the social and gender norms of their era, proving the close connection between political and personal liberation.

Roper’s influence is felt not only in women’s access to education but also in the broader recognition that social movements must include absolutely everyone. Roper’s combination of teaching, activism, and community work transformed education from a privilege into a right.

She died in 1938, but her story reminds us that education is never neutral—it can either reinforce existing hierarchies or dismantle them. Esther Roper chose the latter. She did not just teach; she fought to ensure that every lesson reached those who needed it most.

- https://spartacus-educational.com/WroperE.htm

- https://www.findagrave.com/memorial/14187842/esther-roper

- https://wearewarpandweft.wordpress.com/stature-project/the-women-were-celebrating/esther-roper/