When many Manchester residents think of childhood, they picture toys, playgrounds, and schoolbooks. But in Victorian Manchester, childhood meant something entirely different: early mornings, aching backs, and the endless roar of machinery in the factories. For thousands of working-class children, the Industrial Revolution brought not a happy childhood, but premature adulthood, exhausting labour, and suffering. More on manchester1.one.

19th-century Manchester was at the heart of Britain’s industrial boom. Yet all the wealth flowed to the factory owners, not the workers. This came at a steep price, especially for the city’s youngest inhabitants. Children worked long hours in perilous conditions, often in the same factories as their parents. Their working lives frequently began as early as five or six years old. Read more about the history of lost childhoods in industrial Manchester…

How Children Propelled Manchester’s and the Nation’s Industry

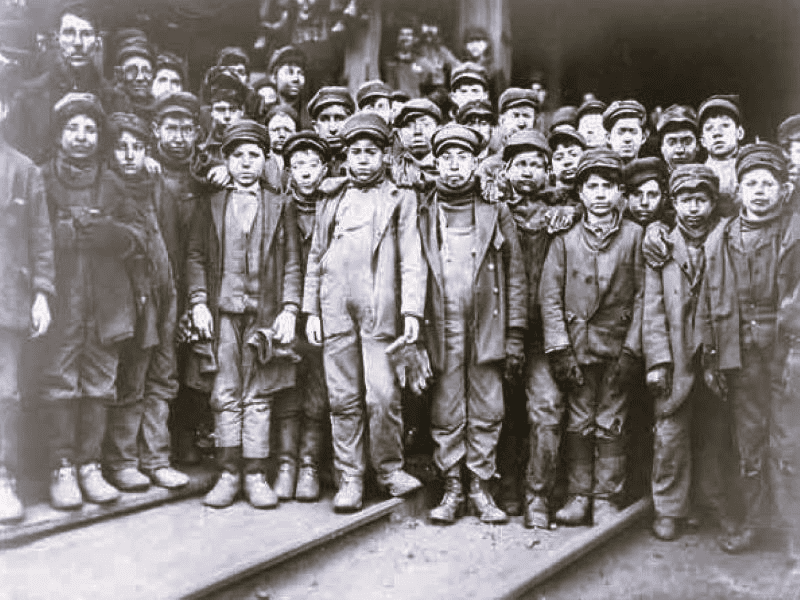

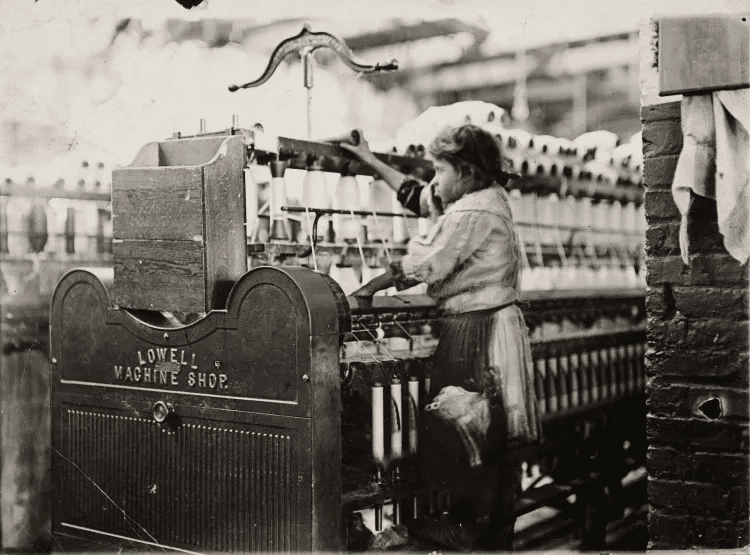

At the height of the Industrial Revolution, Manchester was known as “Cottonopolis.” It was a city driven by textile mills. These factories needed small, nimble hands to clean, repair, and operate machines – and children were ideal. Their size allowed them to crawl under looms, thread bobbins in hard-to-reach places, and collect cotton waste. Employers preferred them for their cheapness, obedience, and reluctance to join trade unions.

Children performed a wide variety of jobs: piecers in cotton mills, chimney sweeps, messengers, and street vendors. But regardless of the profession, the workday was long, and the work was exhausting. Many started their day before dawn and finished only at sunset.

While children from middle and upper-class families learned to read and write, working-class children in Manchester learned how to avoid being crushed by spinning machines or burned by boiling dyes. Education was a luxury few could afford.

Daily Risks Faced by Children

Manchester’s factories were unforgiving. For children, in particular, they were deadly. In cotton mills, the air was thick with fine fibres, leading to lung diseases. Machinery often lacked protective guards, and accidents were common – crushed fingers, maimed limbs, and even death.

Even worse, children were often punished for slowness. Overseers carried canes and were not afraid to use them. Children who fell asleep, unsurprisingly after a 12-hour shift, could be beaten, thrashed, or even locked in a punishment room.

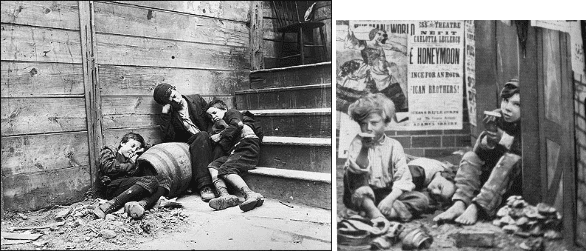

Illnesses such as rickets, tuberculosis, and stunted growth were widespread. Working in cold, damp, and unsanitary conditions, many children suffered not only physically but also emotionally. Life was a vicious cycle of exhaustion and fear.

There were other sufferings too – psychological ones. Constant pressure, threats, and the fear of punishment caused neuroses in children. They grew up without knowing games, care, or time for learning. Many could neither read nor write, as they simply collapsed from exhaustion after their shifts. Childhood passed to the sound of factory hooters, with beatings instead of lessons, and hunger instead of meals.

All of this happened against a backdrop of complete impunity. Employers were rarely held accountable, and only then when a particularly notorious tragedy occurred. But even after a child’s death, the factory most often continued to operate as if nothing had happened.

Nevertheless, children continued to return to work. Not because they wanted to, but because there was no other choice. A child’s earnings could be the only income for a family, especially if the father was injured, ill, or unemployed. A mother working in the same factory could only silently thank fate that her child was alive, despite everything.

These children became the invisible builders of the industrial empire. Without them, there would have been no economic growth, rapid urbanisation, or cheap products. They paid for progress with their health and youth.

But the most terrible thing was that for decades, no one questioned whether children should even be working. It was only towards the end of the century that discussions began about the right to childhood, education, and occupational safety. Until then, thousands of boys and girls in Manchester and across Great Britain woke up before dawn to spend another day amidst the noise of machines and the smell of dust, risking everything for survival.

The Fight Against Child Labour

Not everyone accepted the abuse of child labour as the price of progress. Many figures of that era protested. Perhaps the most famous was Charles Dickens, whose descriptions of child poverty in Manchester and beyond helped awaken national consciousness.

In 1833, the first Factory Act was passed, limiting children’s working hours and setting a minimum age – at least on paper. Inspectors were hired to enforce the rules, but corruption and understaffing meant violations were commonplace.

It took decades of pressure, investigations, and public campaigns before the situation truly changed. Reformers of the time fought for safer working conditions and access to education. Churches and charitable organisations opened Sunday schools and evening classes. Gradually, the idea that children were not just miniature adults, but individuals deserving of protection and opportunities to learn, began to take root.

In 1870, the Elementary Education Act made schooling compulsory for children aged 5 to 13 in Great Britain. This was a turning point. Although the application of the law varied, the very idea that childhood should be defined by education, not by labour slavery, was revolutionary.

The Eradication of Child Labour

By the early 20th century, child labour in Manchester’s factories had significantly decreased. Laws became stricter, schools more accessible, and society more aware of children’s rights.

The story of Victorian Manchester’s child workers is not just a chapter in the city’s history. It’s a reminder of what happens when profit is prioritised over people, and how the most vulnerable suffer the most. It is also a story of resilience, of children who, despite incredible hardships, shaped the identity of an industrial city with their small hands and tireless spirit.

In the 21st century, the factories where children once worked have been transformed into galleries, flats, or offices. Understanding this history helps us appreciate what we now protect and remain vigilant about the rights of children still at risk around the world. For somewhere, the fight for a just childhood continues.

In the 21st century, we admire stylish lofts and industrial heritage, not always considering the price at which these walls entered history. Every brick in an old Manchester building holds the echoes of voices, laughter, and tears of those who spent their childhood by the machines. And although the century has changed, the reality of child labour has not completely disappeared; it has simply changed its appearance. From sweatshops in third-world countries to plantations where teenagers work, the threat of exploitation still exists.

Remembering this means preserving human dignity. Respecting a child’s right to be a child. After all, a just future begins with an honest approach to the past.

- https://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-during-the-british-industrial-revolution/

- https://aithor.com/essay-examples/child-labor-in-victorian-and-romantic-literature-essay

- https://www.quora.com/How-does-Charles-Dickens-show-the-poverty-in-Victorian-time

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/19thcentury/overview/factoryact/

- https://www.parliament.uk/about/living-heritage/transformingsociety/livinglearning/school/overview/1870educationact/

- https://www.arcjournals.org/pdfs/ijsell/v2-i2/1.pdf